This online space keeps evolving! Want to join?

1. WELCOME & INTRODUCTION

Welcome to this Web dossier

Tourism is a major means for presenting ICH which can help sustain it or endanger its community based practice. It is an important source of income and employment. When ICH gains wider attention through safeguarding efforts and UNESCO listings, tourism is often an inevitable result.

Through this web dossier you will find useful tools for developing ICH tourism projects, discussion of key issues, and examples of successful sustainable tourism initiatives.

Find out how communities have developed tourism centred on ICH that represents their culture on their own terms, things to avoid when presenting ICH to tourists, and how anyone working in the heritage sector can enable communities and groups to foster sustainable tourism. There are many useful resources here, including documents of international organisations concerned with ICH and tourism as well as links to publications and online sources on ICH and tourism.

Who is this web dossier for?

It is designed for anyone working in the heritage sector or the tourism field, NGOs and policy workers as well as communities or groups safeguarding their own living heritage.

You can enter this web dossier anywhere on this site. Use it to find successful examples of ICH tourism. It is a living document that will be revised over time – feel free to add examples of successful ICH tourism and share any comments at ichngoforum.research(at)gmail.com

Why focus on living heritage and sustainable tourism?

The relationship between safeguarding intangible cultural heritage (ICH) and tourism might not appear evident to many people, but it is undoubtedly present. Whenever the practice or performance of ICH becomes a destination for travellers who are outsiders to the community of practice, ICH tourism inevitably occurs. Living heritage elements such as foodways or gastronomy practices, handicrafts, arts, local traditions, music and many social practices are often part of what travellers want to discover, depending on their motivations, along with heritage sites and natural landscapes. Travellers everywhere are seeking experiences where they can directly engage with the host community by participating in their activities. They want to taste new foods in local places, respond actively to performances, stay in lodgings in residential neighbourhoods and meet ICH practitioners.

However, the relationship of ICH to tourism requires particular attention because of the potential benefits of tourism for safeguarding and sustaining cultural practices as well as the damaging consequences tourism can have for heritage practitioners and their communities. ICH tourism, when done in proper ways, fits well with the growing trends of experiential tourism, slow tourism and community-driven tourism. The interactions between ICH practitioners and tourism stakeholders can result in better ICH safeguarding, improved livelihoods for local communities, new incentives for heritage skills transmission and exciting new kinds of touristic activities, but it can also threaten the identity or cultural practices and expressions of bearer communities or groups.

Many factors must be considered in order to safeguard intangible heritage and offer sustainable, responsible and quality ICH tourism experiences. These include anticipated assessment of the potential impact of tourism on ICH; safeguarding ICH while allowing for adaptation to changing circumstances; visitor management to address over-tourism; promoting sustainable development including equitable livelihoods based on decent work; development of appropriate products and services linked to ICH; ensuring continuity of traditions; fostering local employment and ownership of tourist enterprises; or educating while entertaining (“edutainment”). Each and every one of these issues ought to be considered and be developed in order to respect the viability of the intangible heritage practices of communities and practitioners involved and give a thoughtful touristic activity.

If not appropriately and respectfully managed in association with the communities impacted, tourism can lead to the degradation of ICH and of the sense of identity of the communities involved, it can provoke great damage to historical and cultural resources and can easily undermine its value(s).1 It can also affect the self-image of practitioners, communities and groups; cause abandonment of their practices and induce such phenomena as gentrification through displacing local businesses and affordable housing, amongst other dramatic consequences.

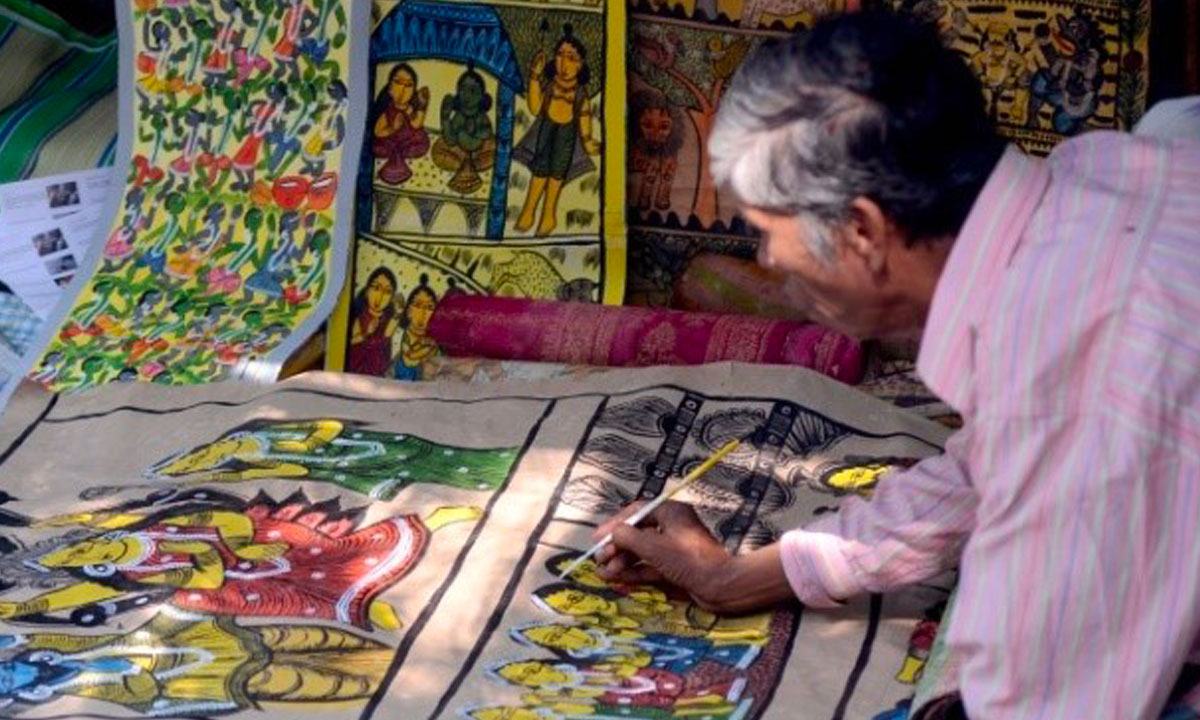

On the other hand, well-designed tourism activities can be beneficial to ICH practitioners and their local community or groups through increasing the economic, social and cultural value of ICH.2 Musicians and dancers perform for new and larger audiences; young people are trained in traditional building practices, crafts and performing arts; local and creative businesses emerge and prosper; and ICH previously ignored or neglected gains new respect and recognition thanks to the interest of tourists.

The UNESCO 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage recognized the need for an official framework to safeguard ICH and aims to give guidelines on this topic. Its Operational Directives (paragraph 187) provided recommendations regarding the safeguarding of ICH in tourism activities. They emphasise the need for tourism activities to respect the safeguarding of ICH and the wishes and needs of host communities. They also balance the interests of tourism businesses, governments and cultural practitioners to ensure the viability, cultural meanings, social functions and sustainability of ICH and promote the adoption of legal, technical, administrative and financial measures, including intellectual property rights, privacy rights and any other appropriate forms of legal protection, to ensure safeguarding. UNESCO also established Ethical Principles which apply to all dimensions of ICH, including tourism development.3 And UNESCO’s Overall Results Framework for ICH links “inclusive economic development”, tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals.4

By diminishing, mitigating and avoiding negative impacts of tourism on its elements, sustainable tourism can bring great opportunities for safeguarding ICH. It must consider the current and future impacts of tourism on ICH, including economic, social and environmental dimensions.5

How can this be done in such a way as to maximise sustainable development benefits to bearer communities, as well as to promote ICH safeguarding?

Sustainable tourism should be developed in a very thoughtful way, in order to respect the living heritage and its practitioners, by adopting strategies aiming to diminish and mitigate the negative impact of tourism without missing out on the benefits. These strategies may include the heritage-sensitive use of intellectual property rights and marketing, as well as digitization strategies. Both tourism and heritage stakeholders should accept that tourism is everywhere, and can therefore affect ICH, and put (more) effort towards the significant redistribution of tourism related revenues to bearer communities. Locally owned tourism businesses should be encouraged and practitioners need to directly benefit economically. There is an urgent need for innovative ideas in line with sustainable development, and approaches that reconcile tourism and safeguarding of ICH. Ethical issues, especially in connection with bearer communities involved, should be addressed in the creation of ethical codes for ICH tourism. It should be a principal focus of our work in the future.

International agencies are more and more aware of bad examples adopted in the past and feel the necessity of giving proper care to ICH and its practitioners.6 In 2015, participants of the World Summit on Sustainable Tourism helped to write The World Charter for Sustainable Tourism +20. This charter demonstrates awareness of this strong link, which is why it claims that “as one of the world’s most powerful economic and social forces, tourism can and must strengthen the decisive role of heritage, both tangible and intangible, in contemporary society, consolidating cultural identity and diversity as key points of reference for the development of many destinations”.7

This toolkit aims to help address these challenges, by offering tools, resources and sharing experiences which may enrich and inspire your future initiatives at the intersection of ICH and Tourism. It provides pathways for ICH practitioners to enable communities to represent their ICH on their own terms to tourists, selectively providing access when appropriate.

- 1 UNESCO Office Bangkok and Regional Bureau for Education in Asia and the Pacific, Establishment Initiative for the Intangible Heritage Centre for Asia-Pacific (2008). Safeguarding Intangible Heritage and Sustainable Cultural Tourism: Opportunities and Challenges. UNESCO-EIIHCAP Regional Meeting, 4. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000178732

- 2 Kim, S., Whitford, M. and Arcodia, C. (2019). ‘Development of intangible cultural heritage as a sustainable tourism resource: the intangible cultural heritage practitioners’ perspectives’, Journal of Heritage Tourism, (14:5-6, 430), pp. 424-425. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2018.1561703

- 3 UNESCO (2018). Operational Directives. Available at https://ich.unesco.org/en/directives

- 4 UNESCO (2018). ‘Guidance Note for Core Indicator 13’, Overall Results Framework. Available at https://ich.unesco.org/en/overall-results-framework-00984#guidance-notes-by-indicators

- 5 United Nations World Tourism Organization. EU guidebook on sustainable tourism for development. Available at https://www.unwto.org/fr/EU-guidebook-on-sustainable-tourism-for-development

- 6 Zhu, Y. and Salazar, N. B. (2015). ‘Heritage and Tourism’, In Meskell, L. (ed.) Global Heritage: A Reader. John Wiley & Sons, Inc 253-254. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/12739602/Heritage_and_Tourism

- 7 World Conference on Sustainable Tourism (2015). World Charter for Sustainable Tourism +20. 19. Available at: http://www.institutoturismoresponsable.com/events/sustainabletourismcharter2015/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/ST-20CharterMR.pdf

2. BASIC CONCEPTS

What is ICH?

“Today, even in a world of mass communication and global cultural flows, many forms of living heritage are thriving, in every country and every corner of the world”8

The 2003 UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) set in motion a growing global movement to sustain cultural practices. It extended efforts to safeguard heritage beyond conservation and protection of physical objects and monuments, defining ICH as: “the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills – as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith – that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals, recognize as a part of their cultural heritage”.9

ICH is transmitted over time and between generations. While it is rooted in the past it is also dynamic, modified, transformed or recreated by communities or groups in relation to their cultural and natural environment.10 ICH is not stagnant, it is a living heritage evolving with people and time, adapting to new circumstances, changing through the creativity of its practitioners. It cannot be frozen in a specific state or period of time.

ICH is found in every human community and group. The 2003 Convention lists some of the domains in which ICH can be manifested as following:11

- oral traditions and expressions, including language as a vehicle of the intangible cultural heritage;

- performing arts;

- social practices, rituals and festive events;

- knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe;

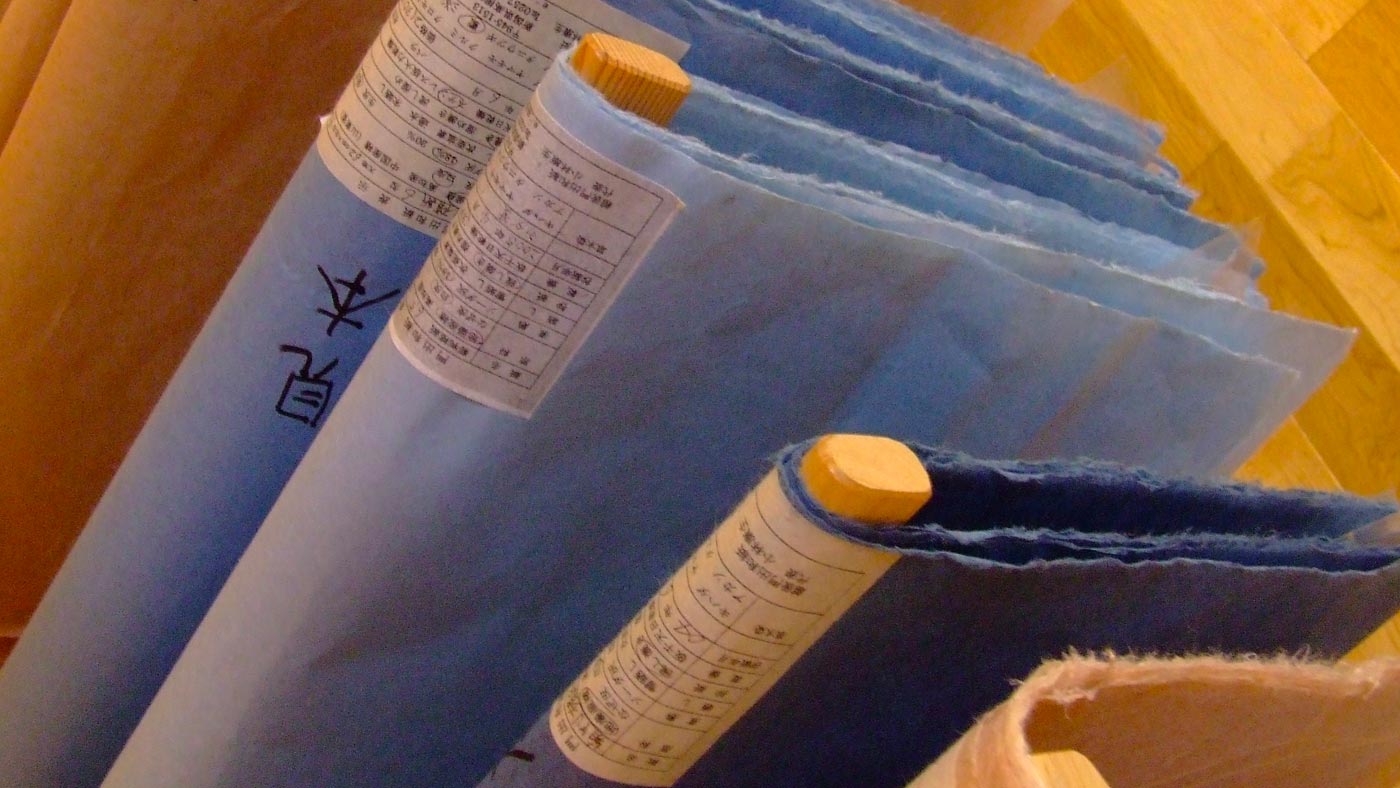

- traditional craftsmanship.

In this toolkit, the expression “living heritage” is used as synonymous with intangible cultural heritage.

- 8 UNESCO Office Bangkok and Regional Bureau for Education in Asia and the Pacific, Establishment Initiative for the Intangible Heritage Centre for Asia-Pacific (2008). Safeguarding Intangible Heritage and Sustainable Cultural Tourism: Opportunities and Challenges, UNESCO-EIIHCAP Regional Meeting. 22. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000178732

- 9 UNESCO (2003). UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available at: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention

- 10 UNESCO (2011). MEDIA KIT – Sixth Session of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (6.COM), 4. Available at: https://ich.unesco.org/doc.src.15164-EN.pdf

- 11 UNESCO (2003). UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage. 2-3. Available at:https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention

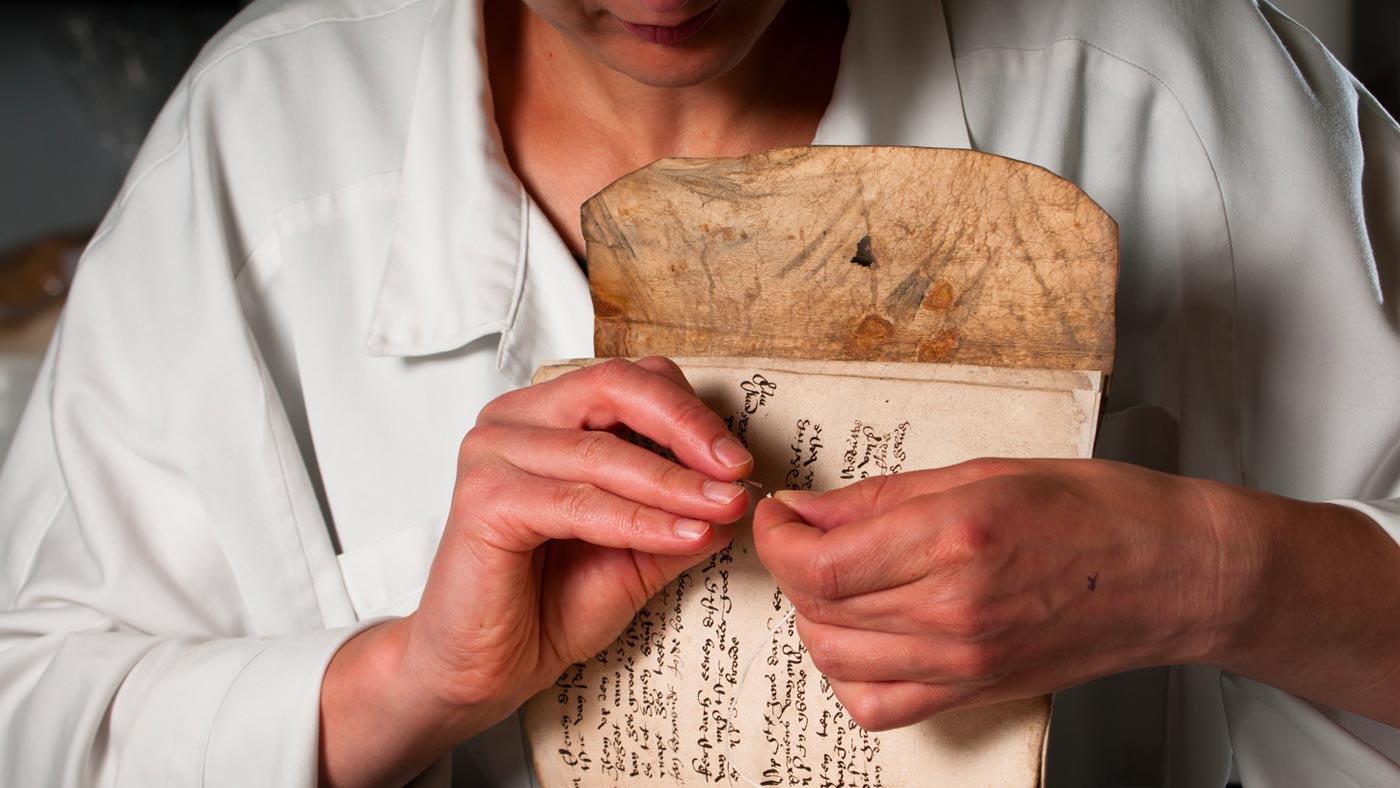

What is meant by ‘safeguarding’?

Since the coming into force of the UNESCO 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, there has been a growing international interest in recognizing, safeguarding and sustaining living heritage for the benefit of current and future generations.

The UNESCO 2003 Convention defines ‘safeguarding’ as actions taken to ensure the viability of ICH. According to the Convention, it can be done via “identification, documentation, research, preservation, protection, promotion, enhancement, transmission” and “through formal and non-formal education, as well as the revitalization of the various aspects of such heritage”.12

Since it is a living heritage, dynamic and constantly changing, ICH should not be safeguarded in a way that freezes or fixes it in one form or another. It is important for ICH that it evolves through adaptations and creativity in response to changing contexts or new circumstances, while remaining within the core values which the community involved attaches to the cultural practice. Safeguarding means transmitting not only the knowledge and skills of the bearers but also functions, values and significance of the living heritage. Safeguarding measures should reinforce this ‘continuous change’ which defines ICH and allow its transmission to future generations.

The UNESCO 2003 Convention, which has been ratified by 180 countries, emphasises the central role of practitioners and their communities, in recognizing the cultural practices they cherish as part of their cultural heritage and in safeguarding it on their own terms.13 Safeguarding measures should emerge, whenever possible, from these bearer communities rather than from a third party that is not committed to the cultural practice and may distort its value. In effect, according to the Convention, any safeguarding measure should be approved by the community or group of people involved.14

Thus, safeguarding ICH is done primarily by the communities, groups and individuals concerned, by those who practise and transmit the heritage. In addition, these community actors can be supported by collaborations among stakeholders that include for example government agencies, NGOs, and cultural specialists.

- 12 UNESCO (2003). UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, 6. Available at: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention

- 13The UNESCO 2003 Convention text uses the encompassing and open concept of ‘communities, groups and -in some cases- individuals’. In recent years you can also find this concept being abbreviated or referred to in the working field of ICH as ‘CGI’.

- 14UNESCO. Safeguarding without freezing. Available at: https://ich.unesco.org/en/safeguarding-00012

What is tourism?

People have travelled since time immemorial, but tourism -travelling for leisure- is a more recent phenomenon. It was born out of modern social trends in 17th century western Europe, although it can be traced back to Classical antiquity and is related to pilgrimage practices in East Asia that began centuries earlier. The World Tourism Organization -UNWTO- defines tourism as “the activities of persons travelling to and staying in places outside their usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business and other purposes.” (UNWTO, 2010). Although there’s not a widely accepted definition, tourism has grown into an industry that includes provision of accommodation, transport, activities, services, food and entertainment as well as education for tourism professionals.

Tourism can take multiple forms

Tourism can take many forms. It can, among others, be heritage centred, agricultural, educational, maritime, sustainable, medical, as well as related to health or wellness, to adventure, adoption from another country of birth, to indigenous life, to sport or to gastronomy, and, as “dark tourism”, to places of death and natural disaster, slum tourism to poor communities or exploitative sex tourism amongst other types of tourism.

According to the UNWTO -The World Tourism Organization- a tourism product is a combination of tangible and intangible aspects; it can involve natural and cultural resources as well as attractions, facilities, services and activities related to a specific interest.15 In 2019, the tourism industry constituted 10.3% and contributed US$8.9 trillion to the world gross domestic product. It represents 330 million jobs around the globe (one in ten jobs) and it is still growing.16

Tourism is one of the most dynamic economic activities in the world, even though the consumption modes have changed in recent years.17 The massive econòmic impact of the COVID 19 epidemic upon tourism worldwide dramatised its significance as an econòmic force.

Depending on their motivations, tourists wish to discover a country and its heritage sites but also its culture, gastronomy, local and social practices and traditions, handicrafts, arts or music. All of these, and many more, are illustrations of what intangible heritage can represent. Many tourists, or visitors, have a growing interest in intangible heritage aspects of a destination such as the ‘everyday culture’, creativity or the arts.18 They are seeking immersive and participatory experiences that provide direct encounters with people from another culture, in non-staged situations, in contrast to the alienating experiences of mass tourism. Tourists are now venturing into less well-trodden regions, staying in Airbnb’s and private homes and eating in restaurants that do not customarily cater to tourists. Such immersive experiences can bring income and opportunity, but can also negatively affect local gathering places, social life and ICH practices in different communities.

In recent decades, sustainability, communitarianism and ethics have increasingly been adapted as principles for tourism development. New tourism actors are born (and with them new labels) and tour operators claim to respect the concepts that accompany sustainable tourism. Sustainable tourism can protect and regenerate the natural environment while also contributing to the safeguarding and revitalization of ICH. It should involve stewardship of heritage by community representatives who decide how ICH is represented and experienced. Sustainable tourism businesses should be locally owned when possible, such as Sherpa owned businesses in Nepal. Tourism agencies and businesses in various places in the world may claim to practice sustainability but engage in a kind of greenwashing and fail to carry out substantive sustainable practices. It’s necessary to ensure that the rights of bearer communities are safeguarded and respected, and to remain vigilant so that this phenomenon does not camouflage mass tourism that could damage the economic, environmental, social and cultural stability of a local population.

- 15 UNWTO. Tourism Definitions. 18. Available at: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284420858

- 16 World Travel & Tourism Council. Economic impact reports. Available at: https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact

- 17 Gomes, A. C. (2015). ORTE2013 Challenging immateriality: Outline for a valuation model of invisible (and visible) heritage. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/ORTE2013-Challenging-immateriality%3A-Outline-for-a-Gomes/483e4fb6596b1d13f7b6a2bb16b307be2297490b

- 18 Gomes, A. C.(2015). ORTE2013 Challenging immateriality: Outline for a valuation model of invisible (and visible) heritage. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/ORTE2013-Challenging-immateriality%3A-Outline-for-a-Gomes/483e4fb6596b1d13f7b6a2bb16b307be2297490b

How does heritage relate to tourism?

Heritage is a major part of tourism, as one of its most significant and fastest growing components. Heritage tourism can touch on religion, historic cities and the built environment, industrial sites, the homelands of ethnic groups living in the diaspora, and the living cultural heritage, among other dimensions of heritage. In some cases, heritage and tourism “have become inextricably linked and mutually depend upon each other”.19

There are many types of ICH, and a wide variety of tourism activities related to these practices. Tourists themselves may want to travel to a certain place for a specific occasion or a traditional cultural event. These includes colourful public events such as the Mexican day of the dead, the traditional Apsara dance in Cambodia, Venice Carnival in Italy, Masai traditional crafts in Kenya and Tanzania, the Holy Week processions in Spain, the Holi festivals in India, the Lyon’s festival of lights in France, Saint Patrick’s Day in Ireland, the beer making of Belgium or the silk crafts in China, to name some examples.

There may thus be as many reasons to visit a place as there are tourists, and many of them are linked to a form of intangible heritage. ICH tourism might bring in benefits to the communities and can help them in their safeguarding efforts. Hosting tourism activities (festivals, events, performances, etc.) can enable promotion of the value of ICH and contribute to its transmission as well as increase the economic, social and cultural value of intangible heritage.20 ICH practices are very attractive to many visitors, but inappropriate activities, over-tourism and intrusive tourism practices can threaten the identity and the transmission of ICH. Also, some forms of ICH are secret and sacred to the communities that practise them, and not intended to be accessible to tourists. Therefore, there is a complex relationship between tourism and ICH, which needs to be carefully managed.

Example: Culinary tourism and culinary living heritage

Certain niches of tourism are particularly linked to forms of expression of intangible heritage. This is for example the case of culinary tourism. Food is an essential part of any trip, and visitors often experience it throughout their visit. It can be the primary purpose of travel but is also present in every type of tourism as part of the visitor’s experience. It may involve intentional exploration of the foodways of the country/region/area visited and it often relates to visitors’ perceptions of what is ‘authentic’, sometimes ‘exotic’, in this form of ICH.21 It illustrates the interest of tourists to explore diverse foodways. Some might want to dare themselves through adventurous eating (the act of consuming something that you wouldn’t usually eat in your own culture) or to discover otherness: a new cooking technique, a food system, a traditional feast, a way of eating or serving, etc.

Culinary tourism can also transform the social practices of a region or city. Tourists may have incorrect preconceptions or assumptions about the region and its culinary culture.22 Practitioners may respond through “recipe adaptation” or “menu selection”, adjusting menus, adapting dishes to make them less spicy, blander or plainer, and even removing some items considered unpalatable by visitors. Practitioners might also change the presentation of food or the decor to meet the expectations of tourists and make their establishment recognizable and reassuring in the minds of visitors. Tourism can thus lead to changes in culinary practices. This might change their local meaning and value, which local communities could view in a positive or negative light. Culinary tourism can in some cases lead to local people developing a new appreciation of local foodways, and the need to safeguard them.

- 19 Zhu, Y. and Salazar, N. B. (2015). ‘Heritage and Tourism’, In Meskell, L. (ed.) Global Heritage: A Reader. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 241. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/12739602/Heritage_and_Tourism

- 20 Kim, S., Whitford, M. and Arcodia, C (2019). ‘Development of intangible cultural heritage as a sustainable tourism resource: the intangible cultural heritage practitioners’ perspectives’, Journal of Heritage Tourism (14:5-6, 430), 424-425. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2018.1561703

- 21 Bortolotto., C and Ubertazzi, B. (2018) ‘Editorial: Foodways as Intangible Cultural Heritage’, International Journal of Cultural Property, 25(4), 409-418. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0940739119000055

- 22 Long, L. M. (2004). Culinary Tourism: A Folkloristic Perspective on Eating and Otherness in Culinary Tourism. The University Press of Kentucky. 21. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287547184_Culinary_tourism_A_folkloristic_perspective_on_eating_and_otherness

3. WHY AND HOW CAN TOURISM ENHANCE OR ENDANGER INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE SAFEGUARDING?

Why is ICH attractive to tourism?

The end of the twentieth century marked a major change in how cultural heritage is viewed. While during most of the century heritage was seen as ‘object-centred’, it shifted to a ‘subject-centred’ approach. Documents such as the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage contributed to these new perspectives on heritage. ICH became more and more visible, popular and experimental, reflecting a trend also in experimental/experiential tourism. This growing interest in living cultural experience, including traditional music, craftsmanship, dance, and foodways is now undeniable. Tourists may wish to discover a country or a region and its heritage sites, while also exploring its gastronomy, festivals, social practices and music, for example.

Tourism practices are changing, as visitors emancipate themselves from big companies and package tours to find their own tourism path. New actors are emerging in the tourism industry, who are not necessarily tourism ‘professionals’. One of the most significant examples is the use of private accommodation options instead of hotel rooms. Airbnb and other homestay services have become a norm when it comes to finding accommodation. Similarly, there is the emergence of ”Food & drink experiences: Cook and Eat with Locals / Unlock Hidden Culinary Traditions” and others related to ICH including crafts. Greeters (locals giving tours to tourists) are becoming the new guides; local communities are welcoming people who wish to experience and participate in ‘everyday life’. Visitors are everywhere and not only in designated areas or zones for tourism because of their desire to discover ‘true’ cultural assets.23

- 23 Gravari-Barbas, M. (2020). ‘Heritage and tourism: from opposition to coproduction’, A Research Agenda for Heritage Tourism. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 4. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4337/9781789903522.00007

How does tourism impact ICH safeguarding?

A complex relationship between ICH and tourism

Tourism can have mixed impacts on ICH safeguarding ⎼ good, bad and both at the same time. There are as many reasons to travel as there are people, and experiencing ICH is a major motivating factor. Tourists seek living heritage as a dimension of travel, especially on trips primarily devoted to heritage or cultural tourism, which are expanding as types of tourism. However, it is important to remember that tourism gives place to an industry (among other effects) that seeks to attain and expand profits from the consumers of their tourism products. It creates tourism offers that seek to respond to the interests of tourists. Frequently, ICH becomes a tourism commodity when it is presented outside of the contexts where it is customarily practised. As a commodity it can bring new sources of income to its practitioners; new markets for crafts and traditional foods; and economic benefits for the community at large. But it can also change cultural meanings when practised primarily for the consumption of tourists and when becoming viewed primarily as an economic resource.24 It can disproportionately benefit local elites and outside investors rather than practitioners and small scale, sustainable local businesses. ICH may become only a commodity for the consumption of tourists, when it ceases to be practised in community-based contexts.25

In some cases, ICH practices which were previously totally devoid of any activity related to tourism became an attraction for visitors as tourism developed, changing the cultural practice for bearers and communities. Even though it can bring revenue to the community and be invested back into local or cultural initiatives, it cannot be disconnected from a loss or change in collective practices and traditions. (Note: Such change is generally appearing gradually; which makes it hard to evaluate and assess such impacts).

Balinese dances, from tradition to tourism

Some Balinese dances performed for tourists are condensed and simplified versions of traditional dances. Some are even new choreographies designed especially for this audience. They often are made accessible to visitors by simplifying linguistic codes, dramaturgic conventions and literary references, which tourists do not know. While these dances now have a different purpose and cultural meaning, they also provide experience and training to the dancers as well as financial benefits.

The revenues are invested back into the practice to buy materials and equipment for dancers performing in the traditional ways for Balinese audiences, out of sight of tourists.26

@ “Balinese dance legong, Ubud Palace, 2013” by Anna & Michal is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Change and transformations are often feared when talking about ICH; nevertheless its essence, as a living heritage, is to evolve with its practitioners, its environment and its time.

This makes processes of ICH tourism in relation to safeguarding often complex, nuanced or ambivalent to evaluate. Tourism often contributes to changes both large and small. Sometimes it leads to an awareness of the importance of intangible heritage and the need to create legal frameworks or use legal mechanisms to safeguard it, sometimes it leads to the realisation that changes are not exclusively negative, and that they can also be perceived as a creative force for communities and their culture.

The Alarde Festival of Fuenterrabia, destruction and construction of ICH

The Alarde Festival of Fuenterrabia commemorates a Basque victory over the French in the 17th century. Until the 70’s, this practice brought all the inhabitants together, regardless of social class, as participation was almost total and its symbolism was of great importance for the town. However, the festival started to be used as a tourism attraction by the municipal government. It became more of a staged event for tourists, resulting in a diminished involvement and interest by the residents for the living heritage practice. The more tourists came to see the festival, the fewer the locals did. The festival lost much of its meaning and value for the community as it became a tourist product performed twice a day instead of once, designed to generate tourism revenue for the town.

So, in the space of two years, the festival, which had been of vital importance for community members, became a tourist attraction. But, over the course of many years, the festival – even in its commoditized form – caused a surge of interest in regional political rights and reflected increased consciousness of regional heritage. Thus, in this case, tourism negatively affected the festival initially, but did later benefit the local community to some extent by increasing social cohesion and local identity.27

@ Alarde_de_Hondarribia (Joanatommy, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

- 24 Zhu, Y. and Salazar, N. B. (2015). ‘Heritage and Tourism’, In Meskell, L. (ed.) Global Heritage: A Reader. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 242. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/12739602/Heritage_and_Tourism

- 25 Zhu, Y. and Salazar, N. B. (2015). ‘Heritage and Tourism’, In Meskell, L. (ed.) Global Heritage: A Reader. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 243. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/12739602/Heritage_and_Tourism

- 26 Picard, M. (1990). ‘”Cultural Tourism” in Bali: Cultural Performances as Tourist Attraction’, Indonesia, 49, 37-74. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/3351053

- 27 Greenwood, D. J. (1977) ‘Culture by the Pound: an Anthropological Perspective on Tourism as Cultural Commoditization.’ in Smith, V. L. (ed., Hosts and Guests: the Anthropology of Tourism. Blackwell Publishers. 129-138, 301 H67:

How can tourism endanger ICH?

Tourism can result in the degradation or loss of traditions along with damage to a heritage community’s identity. This is all the more a risk when tourism developments are poorly planned and insensitive to (often local) culture and interests –whether wittingly or unwittingly. Even though tourism can have short-term benefits, if unplanned or badly managed it can damage resources, whether they are historical or cultural, and undermine their value(s).28 When bearer communities and groups are not adequately involved in tourism planning and development, misappropriations may occur, their rights may not be respected, they may eventually experience a negative self-image, and damage to their cultural values and limited benefits. Some ICH practices have been changed drastically or have disappeared totally after they have become purely touristic performances.

Tourism can radically change the rhythm of the year as a seasonal activity, disrupting and diminishing cyclical cultural practices. It can also cause communities to lose interest in ICH practices or abandon them entirely in favour of a tourism sector that is more lucrative and demands extensive attention. In many places around the world, tourism is a “monocrop”, as happens in the agricultural sector when there is dependence upon a single crop, disasters or unforeseen conditions can devastate an economy. Tourism as a monocrop also means that ICH related to other sources of livelihood lose their presence and functions.29 The great danger of tourism as monocrop was dramatically illustrated during much of the COVID pandemic, which had a disastrous impact upon many communities that rely on tourism as the dominant source of income.

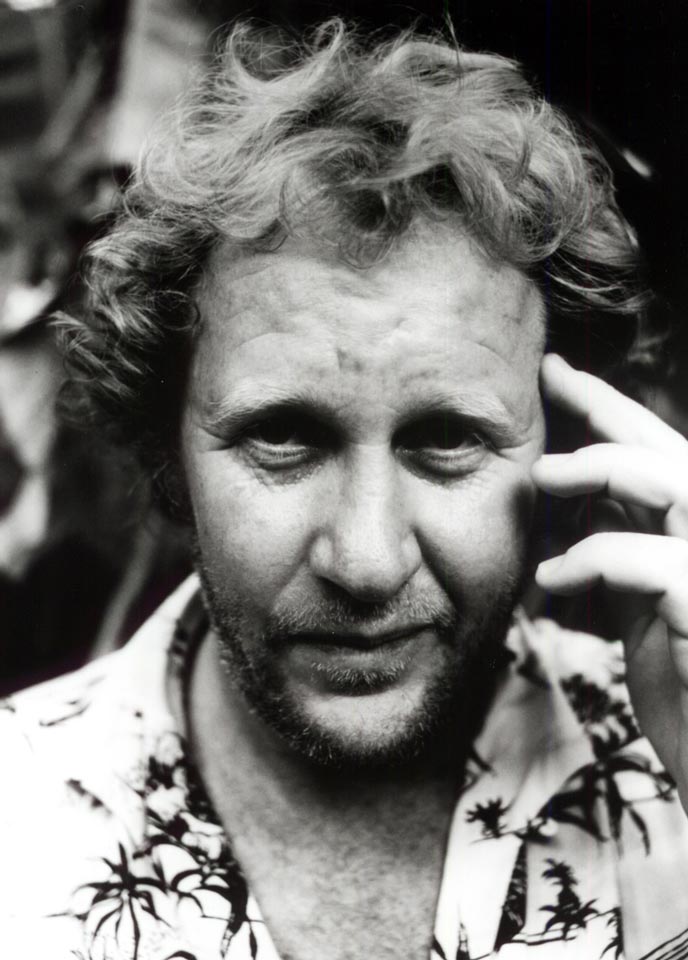

Cannibal Tours

In 1988, as living heritage awareness was growing around the world, Denis O’Rourke filmed an anthropological documentary in Papua New Guinea called Cannibal Tours.30 This film showcases the changes in the local population’s behaviour due to the arrival of tourism, unconsciously disturbing the social stability, the cultural and social practices of Papuans. This documentary highlights tourism management of then shaped distorted cultural representations, when western tourists went on ‘safaris’ amongst the “noble savages”, to use Michel de Montaigne’s word describing an idealisation of Indigenous peoples.31 O’Rourke underlines the voyeurism present in tourism in the 20th century, which can still be visible in some badly managed tourism activities where local populations are showcased in a negatively objectified and commodified manner.

@ “File: Dennis O’Rourke.jpg” by Chris Owen (photographer), Camerawork Pty Ltd (company that owns rights to the photo) is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

When tourism industries are owned and operated by outside interests, without participation of the communities concerned in the planning and decision-making, these people become dependent on a so-called ‘external’ salary, with a loss of autonomy on a local or national basis. And if the number of people working for this business increases, other activities can cease. In places controlled by big tourism companies, family disruptions are often observed as the youngest seek to earn money by leaving their hometowns and their families behind. This phenomenon may involve a massive exodus to where the money is.32 It results in an internal migratory flow which creates an imbalance in the exploitation of natural resources, disrupting the social order and resulting in great damage to ICH. In big cities where tourism represents a big part of the local economy, prices of land, of rent, of admission fees, and the cost of living increase drastically because of the presence of tourists, frequently generating gentrification.33 Inhabitants flee city centres because of this negative impact of urban tourism, and the (sense of the) place itself can change.34

The marketing of Macau’s culinary heritage

The city’s culinary heritage helped make Macau a significant tourist destination in this region of China, partly through marketing of its pastry delicacies. While residents have certainly benefited from tourism activity, rising rentals in the city centre have also, however, pushed many people cheaper locations to the outskirts of the city.35

@ www.flickr.com photos razlan79 3892843298 in photostream

UNESCO’s World Heritage List as well as the Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity became symbols of ‘cultural recognition’ and ‘value’ in the eyes of tourists, even though driving increased tourism was not the objective of these designations. The World Heritage List has even been called an “ever-expanding tourist’s guide to hundreds of wonders in the modern world.” The Lists have had a substantial ‘marketing effect’. It is common knowledge that nomination files for UNESCO Lists are prepared with the hope of attracting an influx of tourists, which generates significant economic benefits. In some contexts not only the understanding seems lacking of what a World Heritage List inscription is supposed to be or to do, but tourism development is even combined with the disappearance of local, traditional cultural practices. Some local governments have taken the matter into their own hands becoming interest groups with their own marketing ideas and policy agendas where profit is the main or only focus, lacking a sustainable management model and appropriate heritage safeguarding measures.36

Touristification of UNESCO Listed heritage

The Summer solstice fire festivals in the Pyrenees were nominated by Andorra, Spain and France and inscribed in the UNESCO Representative List in 2015. The solstice festivals traditionally take place on the 23rd of June (St John’s Day). Once on the Representative List, however, a local government in France changed the timing of the festival, so that it would happen on a Saturday and attract more tourists.

In Spain, the inscription has generated an influx of tourists with an impact on the practice: in the villages concerned, some of the practitioners, especially young people, are mobilised to welcome visitors instead of taking part in the ritual; some then prefer to leave their village to celebrate the ritual in another which is not affected by the inscription; eventually some local authorities decided to close public access to the village during the festival.

@ “Fireworks at the Feux de la Saint Jean Celebration, Perpignan, France” by vic_burton is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

- 28UNESCO Office Bangkok and Regional Bureau for Education in Asia and the Pacific, Establishment Initiative for the Intangible Heritage Centre for Asia-Pacific (2008). Safeguarding Intangible Heritage and Sustainable Cultural Tourism: Opportunities and Challenges. UNESCO-EIIHCAP Regional Meeting, 4. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000178732

- 29El Alaoui, F. ‘L’impact social’, Le tourisme équitable. Available at: https://tourismeequitable.wordpress.com/limpact-du-tourisme-classique/limpact-social/

- 30O’Rourke, D. (1988). Cannibal Tours. 67 minutes, produced by IPNGs.

- 31Montaigne, M. (1962). Essais, I,31. Paris: Garnier.

- 32O’Rourke, D. (1988). Cannibal Tours. 67 minutes, produced by IPNGs.

- 33Zhu, Y. and Salazar, N. B. (2015). ‘Heritage and Tourism’, In Meskell, L. (ed.) Global Heritage: A Reader. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 243. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/12739602/Heritage_and_Tourism

- 34Jeanmougin, H. ‘Gentrification, nouveau tourisme urbain et habitants permanents : des conflits de coprésence révélateurs de “normes d’habiter” divergentes’, Téoros, (1), 39. Available at: http://journals.openedition.org/teoros/4007

- 35United Nation World Tourism Organization (2012), Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage. 55-56. Available at: https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284414796

- 36Zhu, Y. and Salazar, N. B. (2015). ‘Heritage and Tourism’, In Meskell, L. (ed.) Global Heritage: A Reader. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 247. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/12739602/Heritage_and_Tourism

How can tourism enhance and support safeguarding actions?

“The economic gain from tourism can also be highly beneficial for the safeguarding of the intangible heritage”37

The economic, social, environmental and cultural value of intangible cultural heritage can be enhanced through ICH-based (sustainable) tourism for the benefit of communities, groups or individuals concerned.38

From an economic standpoint, tourism based on ICH can provide new employment opportunities to local populations and alleviate poverty. Tourism can become a way to generate new sources of income that remain in the community, through local initiatives, designed to safeguard and enhance ICH for its long-term continuity.39 It often induces community training in tourism tools and management, which could pave the way to generating local tourism businesses, ideally owned by bearer communities themselves who would be able to make their own investment and marketing decisions. It can contribute to rural development when there is minimal ‘leakage’ of the economic benefits.

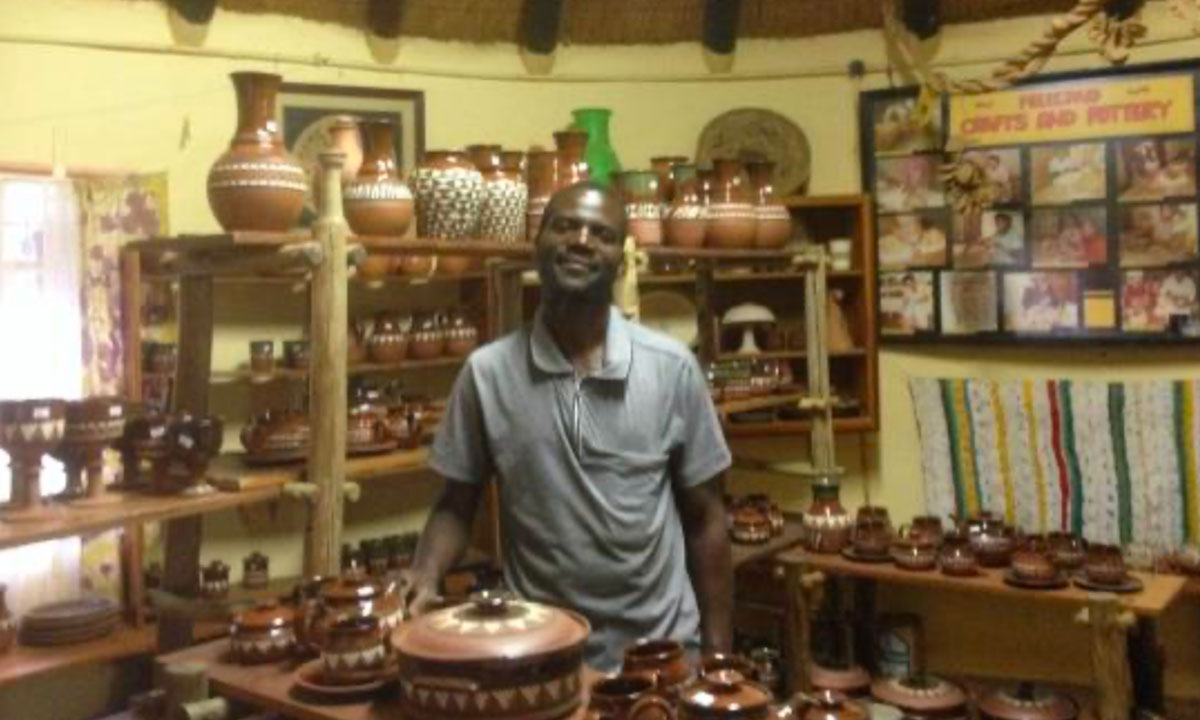

Job opportunities at the Shewula Mountain Camp

In the Kingdom of Eswatini, the Shewula Mountain Camp was established and is fully owned and run by a local community. The Shewula Mountain Camp offers visitors the possibility to discover local ICH such as songs and dances, local crafts and traditional beliefs. All benefits are distributed to the members of the community to develop and improve their daily life. It generates many job opportunities not only in the camp itself but also around HIV/AIDS projects in the area, through its craft centre and Orphan Care Program.

Tourism can reduce rural migration to cities, helping to assure cultural distinctiveness and diversity in an increasingly globalised world. Appropriate management of (sustainable) tourism respects social values of intangible heritage expressions, while finding a balance between educational activities and entertainment in the light of a tourism approach. By involving young generations in the making of these ICH tourism offers, interest in safeguarding is transmitted across age groups, instead of being abandoned by the youngest who tend to leave traditional and rural lifestyles aside.

Sustainable ICH tourism can reduce negative impacts of tourism on the environment by using and managing resources responsibly. Tourism that is both environmentally and culturally sustainable has become increasingly marketable, and it contributes to the well-being of a community.

ICH tourism can create or reinforce a sense of pride within a community or a group by enabling agency for heritage communities in sustaining their treasured traditions. Sustainable and responsible tourism can also allow the transmission of ICH to future generations and can generate a better understanding/awareness about its diversity, safeguarding, preservation, enhancement and sustainability.

Some ICH practices (festivals, performing arts, etc) attract a tremendous amount of people in the same place and therefore induce an increased visibility of such ICH elements and facilitate awareness-raising amongst tourists. Well managed and well promoted, an ICH-specific event can raise awareness among thousands of people who, until then, may not have realised the importance of such an event on a cultural level.

Tourism can also generate space for non-touristic practices of ICH within communities. When in charge of their own touristic offers, they can control the access given to their practices, their lands, their living habits, etc. and maintain traditional customary contexts. This means that there can be ICH activities and culturally significant places that are maintained away from the eyes of tourists, continuing to retain their customary significance for rituals, ceremonies and everyday life. Other kinds of ICH can be presented to tourists on a community’s own terms, where and when presentation to outsiders is felt to be appropriate.

Controlling tourist access to sacred spaces in Australia

In the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, visitors are asked to stay away from sacred sites in the area in order to safeguard the network of paths related to Indigenous sacred beliefs. The management team, which includes Indigenous people, informs tourists of the reasons why they are not allowed to walk past some restricted areas, and educates them on the need to protect and safeguard ICH practices.

@ “Uluru-Kata Tjuta” by alexhealing is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

- 37UNESCO Office Bangkok and Regional Bureau for Education in Asia and the Pacific, Establishment Initiative for the Intangible Heritage Centre for Asia-Pacific (2008). UNESCO-EIIHCAP Regional Meeting: Safeguarding Intangible Heritage and Sustainable Cultural Tourism: Opportunities and Challenges. 30. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000178732

- 38Kim, S., Whitford, M. and Arcodia, C (2019). ‘Development of intangible cultural heritage as a sustainable tourism resource: the intangible cultural heritage practitioners’ perspectives’, Journal of Heritage Tourism, 14(5-6), 431. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2018.1561703

- 39United Nation World Tourism Organization (2012), Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage. 1-7. Available at: https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284414796

4. MORE IN DEPTH - READS

Sustainable tourism

Sustainable tourism, according to the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), is “tourism that takes full account of its current and future economic, social and environmental impacts, addressing the needs of visitors, the industry, the environment, and host communities”.40 Based on social, economic and environmental pillars41, it relates to intangible heritage because of its will to respect and promote these values and to protect the essence of what makes tourism possible to ensure its sustainability for generations to come.

More recently, UNWTO <added the cultural aspect for the understanding of sustainable tourism.</42 This addition of a cultural pillar is what touches on intangible heritage. The social impact promotes a respectful relationship with the involved populations, but the cultural aspect of this new definition touches on the cultural identity and integrity of a group of people.

UNWTO on sustainable tourism:

Sustainability principles refer to the environmental, economic, and socio-cultural aspects of tourism development, and a suitable balance must be established between these three dimensions to guarantee its long-term sustainability.

Thus, sustainable tourism should:

- 1. Make optimal use of environmental resources that constitute a key element in tourism development, maintaining essential ecological processes and helping to conserve natural heritage and biodiversity.

- 2. Respect the socio-cultural authenticity of host communities, conserve their built and living cultural heritage and traditional values, and contribute to inter-cultural understanding and tolerance.

- 3. Ensure viable, long-term economic operations, providing socio-economic benefits to all stakeholders that are fairly distributed, including stable employment and income-earning opportunities and social services to host communities, and contributing to poverty alleviation.

Sustainable tourism development requires the informed participation of all relevant stakeholders, as well as strong political leadership to ensure wide participation and consensus building. Achieving sustainable tourism is a continuous process and it requires constant monitoring of impacts, introducing the necessary preventive and/or corrective measures whenever necessary.

Sustainable tourism should also maintain a high level of tourist satisfaction and ensure a meaningful experience to the tourists, raising their awareness about sustainability issues and promoting sustainable tourism practices amongst them.

Available at: https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-development

Sustainable tourism is a broad concept that includes various forms of tourism: equitable tourism, ecological tourism, ethical tourism, soft tourism, responsible tourism, green tourism, community tourism, solidarity tourism, agro-tourism, etc.43 They all rely on the specific values which tourists share not only with each other but also with the tourism stakeholders that create and put together a touristic offer linking many people together (accommodation, transport, guides, activities, etc.) and generating opportunities of sustainable development for the involved population.

Visitors can be overwhelmed by the range of sustainable tourism opportunities available on the market as more and more companies are elaborating purportedly sustainable products and some stakeholders use sustainability to fulfil economic and political agendas with limited benefit to local communities however. To make sure these offers effectively respect sustainable tourism values, many countries are beginning to develop labels, inscriptions, initiatives or certifications for tourism activities in order to certify their legitimate involvement in the sustainable movement. Some initiatives are national, others are regional (e.g. the European Eco-label advocate the good management of resources, garbage recycling, the use of organic, local green products and food, the European Charter for Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas44, etc) or even global (Green Globe gives a certification to actors that are sensitive to responsible management of cultural heritage, the environment and the economic and social dimensions of a destination)45, involving many types of businesses: lodging, tourism operators, catering professionals, transportation, etc.46 Although they promote sustainability frameworks for heritage tourism, much remains to be done to implement these actions.

Various sustainable tourism forms concern cultural aspects that could be damaged by bad tourism management, but the one that probably reaches the most common ground with the safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage is community tourism. This form of tourism involves populations in the development of local tourism offers made to their benefits. Community members are in charge of building and managing the accommodation structures and the local services. They have complete control over the financial benefits, of which a good part is destined to improve their own life conditions, while respecting nature and tradition.47 Community-driven tourism often offers activities linked with intangible heritage such as handicraft workshops or sharing traditions. Giving opportunities to local populations to manage their own tourism activities is one way to ensure that ICH practitioners are involved in the creation of tourism that fits their needs and thus ensure ICH’s continuity and transmission.

Equitable, responsible, ethical and solidarity tourism also touch upon the cultural aspect of sustainable tourism. The latter engages the responsibility of all actors in order to offer a tourism that is respectful of “human, cultural, economic and environmental resources of the society, that form the life framework of the local communities”.48

- 40 United Nations World Tourism Organization. EU guidebook on sustainable tourism for development. Available at https://www.unwto.org/fr/EU-guidebook-on-sustainable-tourism-for-development

- 41 Van der Yeught, C, (2010). Improving strategic diagnoses: to foster the mutation of tourism destinations into sustainable development ventures. 59-75. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4000/tourisme.321

- 42 United Nations World Tourism Organization. on Sustainable development. Available at: https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-development

- 43 Juganaru, I. D., Juganaru, M. and Anghel, A. Sustainable tourism types. Ovidius University of Constanta. Available at: http://feaa.ucv.ro/AUCSSE/0036v2-024.pdf

- 44 Europark Federation. European Charter for Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas. Available at https://www.europarc.org/library/europarc-events-and-programmes/european-charter-for-sustainable-tourism/

- 45 Green Globe. Green Globe Certification, available at: https://greenglobe.com/green-globe-certification/

- 46 Petit, P. (2017). Tourisme responsable: les labels. Available at: https://www.consoglobe.com/francais-tourisme-responsable-2426-cg

- 47 Juganaru, I. D., Juganaru, M. and Anghel, A. Sustainable tourism types. Ovidius University of Constanta. Available at: http://feaa.ucv.ro/AUCSSE/0036v2-024.pdf

- 48 Juganaru, I. D., Juganaru, M. and Anghel, A. Sustainable tourism types. Ovidius University of Constanta. 801 Available at: http://feaa.ucv.ro/AUCSSE/0036v2-024.pdf

Safeguarding ICH through sustainable tourism

“Culturally as well as ecologically sustainable tourism, along with sustainable development, is a critical issue when heritage is the major attraction of tourism” 49

“Intangible heritage tourism is never an end in itself, and it is always paramount that the intangible heritage communities themselves benefit from actions involving their intangible heritage” 50

Sustainable tourism has many positive impacts on ICH compared to conventional tourism. It aims to respect environmental, economic, social and cultural aspects while allowing visitors to enjoy their holiday. It is a form of tourism that adapts very well to the safeguarding of ICH as it “provides more meaningful connections with local people, and a greater understanding of local cultural, social and environmental issues”51. Sustainable development is generally recommended when safeguarding ICH, regarding tourism or any other activities, as it contributes to “sustainable development for human well-being, dignity and creativity in peaceful and inclusive societies.”52

As already mentioned in the Introduction of this web dossier, from the perspective of heritage safeguarding, tourism can be both an opportunity and a risk. Ensuring positive outcomes requires careful consideration, planning, implementation, and management (Zhu & Salazar). Sustainable tourism should be developed in a very thoughtful way, by adopting strategies designed to diminish tourism’s negative impacts on ICH without sacrificing its positive impacts. By diminishing, mitigating and avoiding negative impacts of tourism on its elements, sustainable tourism can bring great opportunities for safeguarding ICH. It must consider the current and future impacts of tourism on ICH, including economic, social and environmental dimensions. Tourism and heritage actors should face up to the active role of tourism in heritage management and devote more effort to the effective redistribution of the financial benefits of tourism to the communities and groups concerned.

There is a real need for initiatives that join tourism and preservation with sustainability as “more attention needs to be paid to ethical issues, in particular the involvement of local communities, ethical codes of tourism”53. However, international agencies are more and more aware of inappropriate approaches used in the past, and the necessity to better incorporate the “living practices of local inhabitants and their knowledge” (i.e. intangible cultural heritage) in the endeavour to make tourism sustainable and in the actions taken to protect heritage in general.54

What does the UNESCO 2003 Convention say about tourism?

The UNESCO 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, in its Preamble already considers ‘the importance of the intangible cultural heritage as a mainspring of cultural diversity and a guarantee of sustainable development.’ In the course of time, the need for an official framework and to give guidelines on this subject came to the foreground.

Operational Directives, paragraph 187 (see below) provide recommendations regarding the safeguarding of ICH in tourism activities. They emphasise the need for tourism activities to respect the safeguarding of ICH and the wishes and needs of host communities. They also balance the interests of tourism businesses, governments and cultural practitioners to ensure the viability, cultural meanings, social functions and sustainability of ICH and promote the adoption of legal, technical, administrative and financial measures, including intellectual property rights, privacy rights and any other appropriate forms of legal protection, to ensure safeguarding.

UNESCO also established Ethical Principles for the safeguarding of ICH which apply to all dimensions of ICH, including tourism development.55

UNESCO’s Overall Results Framework for ICH integrates “inclusive economic development”, tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals.56

Operational Directives, paragraph 187:

States Parties shall endeavour to ensure that any activities related to tourism, whether undertaken by the States or by public or private bodies, demonstrate all due respect to safeguarding the intangible cultural heritage present in their territories and to the rights, aspirations and wishes of the communities, groups and individuals concerned therewith.

To that end, States Parties are encouraged to:

- assess, both in general and in specific terms, the potential of intangible cultural heritage for sustainable tourism and the impact of tourism on the intangible cultural heritage and sustainable development of the communities, groups and individuals concerned, with particular attention to anticipating potential impact before activities are initiated;

- adopt appropriate legal, technical, administrative and financial measures to:

- ensure that communities, groups and individuals concerned are the primary beneficiaries of any tourism associated with their own intangible cultural heritage while promoting their lead role in managing such tourism;

- ensure that the viability, social functions and cultural meanings of that heritage are in no way diminished or threatened by such tourism;

- 49 UNESCO Office Bangkok and Regional Bureau for Education in Asia and the Pacific, Establishment Initiative for the Intangible Heritage Centre for Asia-Pacific (2008). Safeguarding Intangible Heritage and Sustainable Cultural Tourism: Opportunities and Challenges. UNESCO-EIIHCAP Regional Meeting, 28. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000178732

- 50 Van der Zeijden, A., Neyrinck, J., Adams, K. M., Van Ouwerkerk, F., Van Gorp, B. and Catteeuw, P. (2020). ‘Intangible heritage as a tourist destination. Contribution to safeguarding intangible cultural heritage through sustainable tourism’, Volkskunde, 121(4).

- 51 UNESCO (2018). Overall Results Framework for the 2003 Convention. Available at: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/41571-EN.pdf

- 52 UNESCO (2018). Overall Results Framework for the 2003 Convention. Available at: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/41571-EN.pdf

- 53 Zhu, Y. and Salazar, N. B. (2015). ‘Heritage and Tourism’, In Meskell, L. (ed.) Global

Heritage: A Reader. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 253-254. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/12739602/Heritage_and_Tourism - 54 Zhu, Y. and Salazar, N. B. (2015). ‘Heritage and Tourism’, In Meskell, L. (ed.) Global

Heritage: A Reader. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 253-254. Available at:https://www.academia.edu/12739602/Heritage_and_Tourism - 55 UNESCO (2018). Operational Directives. Available at https://ich.unesco.org/en/directives

- 56 UNESCO (2018). ‘Guidance Note for Core Indicator 13’, Overall Results Framework. Available at https://ich.unesco.org/en/overall-results-framework-00984#guidance-notes-by-indicators

What does sustainable tourism look like in the context of ICH?

-

Sustainable tourism follows ethical principles, contributing to cultural sustainability

The 2008 Regional Meeting for Safeguarding Intangible Heritage and Sustainable Cultural Tourism held in Bangkok by the UNESCO Office Bangkok and the Regional Bureau for Education in Asia and the Pacific underlined that by generating financial benefits, the tourism industry can strengthen the self-respect of local populations as well as their values and identity, which contributes to the safeguarding of their ICH elements.57 This is aligned with UNESCO’s Ethical Principles for the safeguarding of ICH.58 The utmost consideration should be given to ethical principles and professional conduct. Ethical principles for engaging with ICH focus on its valuing, its beneficiaries, access, impact, threats, respect and diversity, …. and can be signposts for understanding how to go about.

Mapping ICH and branding ICH tourism offers are, from a tourism perspective, efficient ways to identify local, regional or national assets, to increase the sense of pride amongst community members, to raise awareness on specific ICH elements and most of all to promote ICH safeguarding. -

Sustainable tourism is community led

Practitioners and bearers are best able to ensure the respect of a cultural practice or to decide how it should be put forward, or branded, in order to ensure its safeguarding for future generations. The World Charter for Sustainable Tourism +20 states that local communities should thus be empowered and involved in planning and developing tourism activities. Scholars report that empowerment of ICH practitioners facilitates the development of tourism strategies suiting each ICH element. Today, the unequal relationship between tourism stakeholders and ICH practitioners is often the reason why its safeguarding isn’t effective.61

-

Sustainable tourism creates equitable, economically stable benefits for (local) communities

Sustainability presupposes a fair approach to sharing economic benefits among all stakeholders in a tourism initiative. In the context of ICH, this implies that particular attention should be paid to the bearer communities concerned. Indeed, UNESCO’s 7th Ethical Principle for the safeguarding of ICH states that “The communities, groups and individuals who create intangible cultural heritage should benefit from the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from such heritage, and particularly from its use, research, documentation, promotion or adaptation by members of the communities or others.62

-

Sustainable livelihoods from tourism depend on diversified sources of income

Tourism can be rapidly affected by political, economic or environmental factors, such as a recession or a pandemic, or a decline in the popularity of a destination. Thus, tourism should ideally not be the sole source of income for local communities. It should not be a monocrop, like a single crop vulnerable to econòmic disaster when a harvest fails because of weather or other unforeseeable conditions.

-

Sustainable tourism development planning that depends on ICH is not the same as ICH safeguarding planning

People and organisations engaged in tourism development may have different interests from those aiming to safeguard the ICH, even if both depend on the existence of the ICH. These different interests and dependencies should be mapped out, and common aims and goals identified that achieve the best possible outcome for both. A “parallel relationship strategy could achieve the safeguarding of ICH cultural values while concomitantly facilitating the socio-economic value of ICH via the commercial promotion of ICH”.63 However, there is not a hard and fast dichotomy between actors engaging in safeguarding and commercial purposes. For example, ICH bearers seek to market their crafts or reach new audiences with their music while retaining the integrity of their traditions, conjoin these two roles.

-

Sustainable tourism promotes ICH practices in a way that is environmentally sustainable

The UN’s 2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals promote the development of sustainable tourism and make it a point of honour to promote local culture and products, and thus: intangible heritage. Sustainable tourism should ensure optimal use of environmental resources and ensure that ICH tourism activities do not increase the environmental footprint. Tourism should be a factor of sustainable development that emphasises both natural environment protection and reinvestment of the revenue into heritage. Tourism uses of the cultural heritage of humankind should contribute to its enhancement. ICH practices are in many cases sustainable in themselves, contributing to a generally positive image of the destination as they rely on human workforce (small numbers) and a healthy relation to its environment, especially when it comes to food security and land use. Centuries of practice have taught people how to use their environment in a manner that maintains a balance within available resources. This is key to sustainability.

However, also increased demand for ICH products and new pressures such as climate change can overstretch natural resources, so the impact of ICH practice on the environment as well should be constantly monitored and managed.

- 61 Kim, S., Whitford, M. and Arcodia, C (2019). ‘Development of intangible cultural heritage as a sustainable tourism resource: the intangible cultural heritage practitioners’ perspectives’, Journal of Heritage Tourism, 14(5-6), 432. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2018.1561703

- 62 UNESCO (2015). Ethical Principles for Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available at: https://ich.unesco.org/en/ethics-and-ich-00866

- 63 Kim, S., Whitford, M. and Arcodia, C (2019). ‘Development of intangible cultural heritage as a sustainable tourism resource: the intangible cultural heritage practitioners’ perspectives’, Journal of Heritage Tourism, 14(5-6), 432. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2018.1561703

Monitoring and Evaluation of sustainable tourism, and its relation to ICH

In 2004 the UNWTO published the first Guidebook dealing with indicators of Sustainable Development for Tourism Destinations64, which also initiated a process of measuring the sustainability of tourism (see below).65 In its framework, sustainability is addressed via the 3 aforementioned pillars of (1) optimal use of environmental resources, (2) respect of socio-cultural authenticity of host communities and (3) economic benefits for all stakeholders. The Guidebook has been influential in creating a better understanding of the relationships between ICH and tourism, emphasising the centrality of the host community. The monitoring methodology depends heavily on participatory processes, and the use of indicators for assessing the impact(s) of tourism on local communities as well as on visitors (p. 22-54 Key Steps to Indicators Development and Use).

This approach suggests possible ways of representing tourism impacts on safeguarding under the Overall Results Framework of the UNESCO 2003 Convention, which was developed in order to assess the impact of safeguarding activities under the Convention in different countries.

Developing indicators for monitoring purposes could thus be beneficial for sustainable tourism as well as for safeguarding processes.

The following parameters from the Guidebook (section 3) can be considered when planning tourism activities related to ICH from a local and community-based perspective (even though there is nothing in these parameters that specifically measures the impact of tourism on practice and transmission of ICH, the absence of which is to be noted):

- Wellbeing of host communities including:

- Local satisfaction with tourism (Attitudes, dissatisfaction, community reaction)

- Effects of tourism on communities (Community attitudes, social benefits, changes in lifestyles, housing, demographics)

- Access by local residents to key assets (Access to important sites, economic barriers, satisfaction with access levels)

- Sustaining cultural assets

- (Cultural sites, monuments, damage, maintenance, designation, preservation)

- Community participation in tourism

- Community and destination economic benefits

- Limiting impacts of tourism activity including:

- Controlling noise levels

- Managing visual impacts of tourism facilities and infrastructure

- Controlling tourist activities and levels including:

- Controlling Use Intensity (stress on sites and systems, tourist numbers, crowding)

- Managing events (sport events, fairs, festivities, crowd control)

- Destination planning and control

- (integrating tourism into local/regional planning)

Addressing wellbeing of host communities is directly linked to ICH as it encompasses the daily activities of communities, which inevitably involves ICH practices. As suggested in the Guidebook “… actions by the industry to maintain a positive relationship between hosts and tourists can anticipate and prevent incidents and negative effects.” The same goes for ICH practitioners. As members of a host community they are entitled to set limits to the activities initiated by the tourist sector in order to prevent loss of privacy or change of lifestyles.

In the context of ICH, access can be viewed as access to information and/or public spaces. Access to public spaces is sometimes denied or restricted for locals after tourism initiatives are put in place. These can be sacred sites but also places where people gather for festive or social events. Tourism has taken over many historical and attractive spaces which a few years ago – and in some countries with long tourism tradition even for decades – were part of everyday local practices, preventing the viability of the practice or altering its performativity.

Community participation and management (that integrally involves communities and groups of ICH practitioners if directly addressed by a tourist plan) is key to all aspects of sustainable ICH tourism production. If actively participating they can contribute to urban planning and visual impacts (building techniques and knowledge about nature, crafts), managing events (rituals and performing arts) directly influencing the viability of the practice and planning in general if an ICH element is the basis for a tourist destination.

Even though the guidelines for developing sustainable tourism do not directly address ICH, they can be applied to measures to prevent harmful actions to host communities through tourism. Accordingly, actions to raise awareness on the challenges, risks and opportunities tourism brings to ICH practices should be encouraged in order to prevent damage and reinforce safeguarding.

Measuring the sustainability of tourism

With the support of the United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD), UNWTO has launched an initiative, Towards a Statistical Framework for Measuring the Sustainability of Tourism (MST). The aim is to develop an international statistical framework for measuring tourism’s role in sustainable development, including economic, environmental and social dimensions.

Such a standards-based framework can further support the credibility, comparability and outreach of various measurement and monitoring programmes pertaining to sustainable tourism, including the utilisation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) indicators and UNWTO’s International Network of Sustainable Tourism Observatories (INSTO).

Overall, the statistical framework from the MST will provide an integrated information base to better inform sustainable tourism, to facilitate dialogue between different sectors and to encourage integrated, locally relevant decision making.

The MST will also foster future dialogue with the ICH sector, especially via the potential links to be elaborated with the Overall Results Framework.

- 64 United Nations World Tourism Organization (2004). Indicators of Sustainable Development for Tourism Destinations A Guidebook. Available at: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/epdf/10.18111/9789284407262

- 65 United Nations World Tourism Organization. On Measuring the Sustainability of Tourism. Available at: https://www.unwto.org/standards/measuring-sustainability-tourism

5. FIRST STEPS TO ACTION

General objectives and guidelines for ICH tourism

General objectives and guidelines for ICH tourism

- Bearer community involvement: bearer communities and practitioner groups should always be involved in the development of tourism related to their ICH, through strong and trusting partnerships based on communication, transparency and knowledge sharing.

- ICH safeguarding: Safeguarding measures should always be taken into account when developing ICH tourism. Tourism activities should ideally enhance (and certainly not threaten) the viability of the living heritage practice and promote its meaning and value to the communities concerned.

- Design of the tourism offer and assessment of impacts: The impacts of the development of any ICH tourism offer, both positive and negative, should be assessed with the participation of the bearer communities, groups and individuals concerned. Their participation should be planned prior to any development as well as in follow-up of the implementation (monitoring and evaluation).

- Respect of sustainable development objectives and approaches: ICH tourism should be thought of with sustainable development in mind, with respect to the social, cultural, economic and environmental aspects of sustainability.

- Respect the value and meaning of ICH elements: The value and meaning of any ICH element presented in a tourism offer should always be respected, whether in its development or in the product itself. Heritage-sensitive design needs to reflect on the kinds of value and meaning the community wants to communicate, as well as the synergies between a tourism activity and safeguarding priorities.

- Avoid over-commercialization and decontextualization: Inappropriate change and loss of social context and meaning associated with an ICH element through tourism activities should be limited.

- Give back to bearer communities: Bearer communities or groups should be the main beneficiaries of any perceived financial or economic benefits that may arise from the development of ICH tourism. Ownership of tourism businesses should reside within the bearer’s own community whenever possible.

- Recognize and respect the customary rights, practices and expressions of communities: Forms of legal protection, such as intellectual property rights and privacy rights, should be provided to ICH practitioners, bearers and their communities to ensure their ICH is not exploited by others for commercial or other purposes. The importance of customary rights of communities to spaces necessary for the practice and transmission of ICH should be recognized in tourism policies and/or legal and administrative measures.

A checklist about planning for a tourism initiative actively centred on ICH

Planning the development of a tourism initiative centred on safeguarding intangible cultural heritage may at times seem complex. The impacts and consequences, both negative and positive, are considerable and need to be properly addressed.

Here is a checklist of actions that can contribute to an efficient ICH safeguarding when developing a tourism offer:

-

Ensure that bearer communities are leaders in the development of a tourism offer related to their ICH by:

- Ensuring bearer community involvement through strong and trusting partnerships based on communication, transparency and knowledge sharing.

- Ensuring that a range of ICH stakeholders (e.g. practitioners, groups, associations, …) are involved and consulted.

- Supporting bearer community engagement from A to Z, in the consultation process, creative phase, strategy and goals development, management phases, etc. Develop programs that equip community members to direct tourism activities and own local tourism businesses.

- Empowering bearer community members, where needed, with the skills and knowledge to drive and direct in tourism-related planning, implementation and monitoring activities

-

Assess the potential impacts of tourism and manage risks and threats properly by:

- Supporting communities to determine impacts, and to identify what constitutes a threat to their ICH, “with particular attention to anticipating potential impact before activities are initiated” (par. 187 of the 2003 Convention’s Operational Directives).

- Elaborating a strategy regarding threats to be managed or mitigated thereafter.

- Defining indicators to monitor and assess impacts, and on the roles of each stakeholder involved in this process.

- Avoiding any action threatening ICH safeguarding.

- Learning about what is working and what is not. Monitoring and analysing the results of such tourism interventions with the communities or groups.

- Adapting the tourism offer to better achieve community-identified goals and results.

-

Respect the rights of communities and groups that create, bear and transmit ICH by:

- Creating guidelines and regulations which respect the interests of sustainable tourism and the rights of communities.

- Respecting customary restrictions on access to ICH (such as a sales ban on certain ICH-related objects, or the restriction or denial of access to certain rituals and places within the host community).

- Where appropriate, using community centred intellectual property rights, moral rights or other legal frameworks to protect the interests of communities in respect of their ICH, and avoid third parties to wrongly acquire IP rights over ICH.

-