By Albert van der Zeijden, Dutch Centre for Intangible Heritage (VIE)

The Dutch Centre for Intangibe Heritage, the organization I work for, is responsible for the implementation of the UNESCO convention in the Netherlands. This means that we are assigned by the Dutch government to make a National Inventory of Intangible Heritage present in the Netherlands and that we support the communities in their heritage care. The way we go about is as follows. Communities can put forward something for the National Inventory, accompanied by a heritage care plan. The idea behind this is that it is up to the communities to decide what they want to safeguard. And that the communities themselves are actually involved in the safeguarding. The role of the Dutch Centre for Intangible Heritage (VIE) is to help and support them and, more in general, to develop safeguarding methodologies.

At present forty elements are inscribed on the Dutch National Inventory. In this article I want to focus on the eight religious traditions on our National Inventory. What VIE noticed is that religious heritage needs special attention. Like everywhere in Europe, these eight religious traditions on our National Inventory are confronted with the process of secularization – which according to sociologists is perhaps inextricably intertwined with the process of modernization and industrialization that started in the nineteenth century. This means that less and less Dutchmen feel attracted to the traditional religions in the Netherlands, that is Protestantism and Roman Catholicism.

At the same time outside these traditional religions all kinds of new forms of spirituality are experimented with. How can you keep a religious tradition alive if less and less people have experienced the old tradition within its original religious context or no longer feel attracted to the religious message behind it? In this article I present some of the safeguarding plans that the communities themselves have put forward. They might be of interest to communities in other countries dealing with the same challenges. Roughly speaking five possible strategies will be discussed:

- new ways of presenting the old story for young people;

- new and alternative meanings in line with the old tradition;

- different forms, new experiences;

- theatrical renewal;

- opportunities in connection to spiritual renewal.

Deep historical roots

On the Dutch National Inventory the eight religious traditions inscribed are:

- the Blessed Sacrament Procession in Boxmeer;

- children singing from door to door (1. during Saint Martin and 2. during Epiphany);

- All Souls;

- Hanukkah;

- psalm singing in Genemuiden;

- the religious pilgrimage the Sjaasbergergank, in the southern part of Limbourg;

- the passion plays in Tegelen.

Most of these traditions have deep historical roots. The ‘Boxmeerse Vaart’, for instance, is a religious tradition which dates back to a blood miracle in the fifteenth century. In this respect it is comparable to other religious processions all over Europe, like the famous blood procession in nearby Bruges, in Flandres, which is on the international representative list of UNESCO. Other traditions are more recent, like the Sjaasbergergank, dating back to the eighteenth century. All Souls, dating back to the Middle Ages, got its new form of visiting the graves during the nineteenth century. In Mexico it is called the Day of the Dead and this particular Mexican way of celebrating All Souls is also on the International UNESCO list. Holy feasts as Saint Martin and Epiphany also have medieval roots, but like the Jewish feast of Hanukkah got a new momentum during the nineteenth century when also Christmas became more important as a family feast all over Europe. The Passion Plays in Tegelen nicely fits in with the period of ‘spectacularisation’ of the catholic religion in the first part of the twentieth century. In Tegelen the passion of the Christ was given a theatrical translation into a hugely popular theatre event, in the open air theatre of this village in Limbourg. Last but not least we have a protestant tradition on our National Inventory: the ‘bovenstem zingen’ in Genemuiden, a special way of singing psalms in or outside the church, also dating back to the eighteenth century.

All these traditions had their heyday from the eighteen eighties to the nineteen sixties. From then on, secularisation set in. At present the older generations who were raised with these traditions are rapidly dying out so it is time to find new meanings for these old traditions that might otherwise disappear. Which plans have the communities come up with?

Telling the old story anew

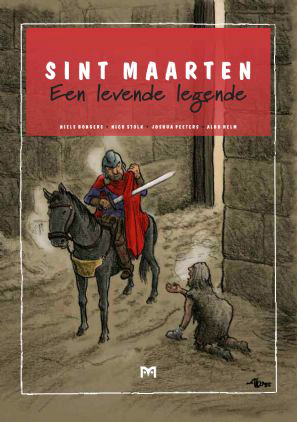

As a saint, Martin is famous all over Europe. All kinds of traditions have evolved in connection to this saint. In some parts of the Netherlands children used to go from door to door. They sang traditional Saint Martin songs in return for sweets. The Saint Martin Committee in Utrecht tries to find new ways of communicating the old story of Martin, who cut his cloak in half to help a poor man. One of the ways was by means of comics, with attractive and colourful drawings. Comics are very popular with youngsters and there are more religious traditions that use this method of telling the story anew.

But what the Saint Martin Committee finds even more important is keeping the spirit behind Saint Martin alive. Saint Martin is about helping the poor. This is why the Saint Martin Committee organises special activities for the poor and needy. One of these activities is that all homeless people in Utrecht are invited to a free hot meal at the Sleep-inn/Het Smulhuis. By presenting Saint Martin as the feast of sharing with the poor, the feast is given a more secular meaning but one that is in line with the old tradition.

In addition to this all kinds of cultural activities are organised, for instance light processions for the children, exhibitions in the museums in Utrecht, a Saint Martin Fair and carillon concerts. With these activities, organised in cooperation with museums, schools and cultural organisations, the organizing committee hopes to attract tourists. For this they receive a strong support from the city council and from local tourist organizations. The Saint Martin Committee tries to cooperate with as many partners as possible, so as to give a broader and sounder foundation to the Saint Martin festivities.

The trend is to ‘culturalise’ your event, that is to organise cultural festivities alongside your tradition. Also the promotional aspect, tourism, is considered very important. The challenge is to safeguard the atmospheric picture of the old days and at the same time transform it into something that is also attractive for youngsters. In the case of Driekoningenzingen in Mid Brabant it was in the sixties that local tourist organisations in cooperation with the schools organised a special song competition. A competition is definitely a way to involve a younger generation. In Brabant there is also much attention for telling the story behind Epiphany anew, especially as now a broad array of youngsters from different ethnic and religious origin are among the pupils at school not familiar with the tradition but might feel attracted to a more general meaning connected to the feast.

A change of focus

The same thing goes for the religious procession in Boxmeer and the pilgrimage the Sjaasbergergank in Valkenburg. More than Saint Martin (and Driekoningenzingen), these traditions used to be predominantly religious in nature and character. In Boxmeer they have opted for a change of focus from exclusively religious to a feast that has also cultural significance and is important for the cultural identity of Boxmeer. The organisers want to position the Boxmeerse Vaart ‘as cultural heritage, as a monument’ which might even improve the attraction value of Boxmeer in a touristic sense. This is the main reason for choosing a new logo and this is also the reason to cooperate intensively with the city council and with local tourist organisations. In itself the Boxmeer procession is a spectacle, attractive to look at.

The same thing applies to the Sjaasbergergank, the religious pilgrimmage in Valkenburg in the province of Limbourg. In Valkenburg, there is a connection between the spectacular and the touristic also. The organisers of the Sjaasbergergank want to stick to the pilgrimage as a religious event, with among other things an open air Holy Mass celebration and the traditional blessing and the distributing of the so-called ‘Teunisbroodjes’.At the same time they cooperate with the tourist sector and stress the historic heritage value of the event. In this case local identity and experience economy go hand in hand. It gives the local community a possibility to cultivate their local identity in a form that is attractive for tourists.

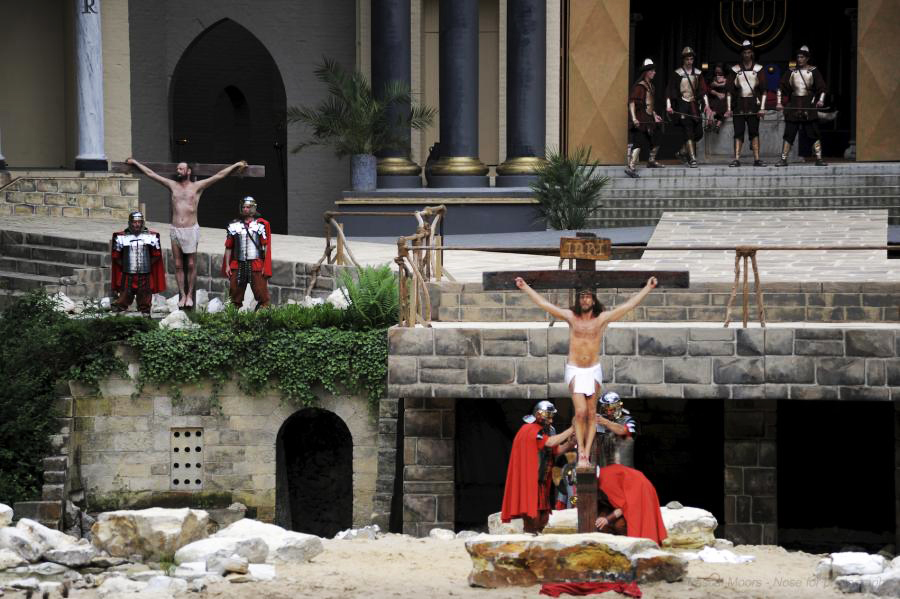

To add even more dignity to the procession in Boxmeer, the organising committee of the Boxmeerse Vaart has assigned artists to make bronze life like statues alongside the route, which represent the participants in the procession: the angels, the altar boys, the youngsters dressed up like little brides of Christ. Art is used to reinforce the attractiveness of the procession. Theatrical renewal could be another option. This is for instance the case with the Passion Plays in Tegelen. To attract younger and newer audiences the text of the play is now and then revised or refreshed. In Tegelen they engage text writers to make a new and fresh script with present-day dialogues that appeal to new generations. Nowadays the focus is on the emotional aspect of the passion. People like to identify themselves emotionally with the main characters in the play. They want to see real passion and real pain, but also redemption and catharsis. This is what they get at Tegelen.

At the same time the cultural roots aspect remains important. This is for instance the case with the Jewish feast of Hanukkah. Of course this feast has a religious background. At the same time it is important for the cultural identity of the Jewish community. This is also how it is put in the proposal for the National Inventory: the feast is important because youngsters might want to learn more about their cultural roots.

Spiritual renewal

One last option is still to be discussed: to use the growing popularity of new forms of spirituality in the Netherlands. Whereas the old, traditional religions seem to be on the decline this does not mean that people aren’t interested in the spiritual side of religion. There is a strong current of experiencing religion outside the traditional churches, demonstrated in the emergence of spiritual movements like New Age. To the organisers of the ‘old’ traditions it offers an opportunity to attract attention from outside their own religious community. In short: they hope to attract more popular attention by presenting their tradition in a more general, spiritual way that might attract these other people. The tradition of Psalm singing in Genemuiden offers a nice example. This way of psalm singing is very traditional and conventional. In Genemuiden, situated in the conservative Dutch Bible Belt, people are still regular churchgoers. All the same these local choirs bring out cd’s with their music which are also attractive for others, outside their religious community. In their proposal and heritage care plan for the National Inventory the local community refers to a ‘wondrous dimension of singing which connects us to the origin of man’. It makes you think of the monks of Solemnes, in France, with their very popular Gregorian chanting. There is a growing need for a new spirituality and the psalm singers with their unusual way of chanting may well create a hype, just like the monks of Solemnes.

New spirituality and new ways of dealing with religious or spiritual questions also come up in new ways of celebrating All Souls. Where Catholicism has lost much of its meaning in the Netherlands, there is at the same time a growing demand for rituals in connection with death and bereavement. And where the church has left a vacuum, the cemetery directors are filling the gap. Helped by ritual specialists and sometimes by artists these cemetry directors organise special rituals like light processions or remembrance concerts and special practices where the bereaved can light a candle and put it on the graves of their loved ones. The crematorium at Driehuis Westerveld was one of the first to organise a special requiem concerto on a yearly basis. For the participants

All Souls has got a new spiritual meaning, no longer directly attached to the Roman Catholic Church. In view of this it is no coincidence that the proposal of All Souls for the National Inventory was not made by the church, but by a heritage organisation which also takes care of the heritage aspect of the graves and now takes responsibility for traditions on the cemeteries, including All Souls. The proposal was seconded by the National Foundation of Cemetery Administrators, the LOB, and the Funeral Museum in Amsterdam – as to emphasize even more the heritage aspect of the proposal.

How to make your ICH attractive for future generations?

The organisers of the above mentioned traditions are looking for new ways and new forms that might make their traditions attractive for new generations. There is a couple of lessons you can take from this if you want to develop a more general safeguarding methodology for these or comparable religious traditions. From the above mentioned examples we could deduce a number of possibly critical factors that might help to safeguard religious traditions. These are some suggestions that might prove useful:

- try to give a more general and ‘spiritual’ meaning to your tradition, which might also be attractive to groups and individuals outside your own religious community;

- try to invent new forms that might be appealing to younger generations;

- don’t restrict yourself to one denomination only and try to disentangle yourself from rigid church structures that might alienate others;

- try to strengthen your tradition by including cultural activities connected to your tradition;

- cooperate with other stakeholders: heritage institutions, city councils, local tourist organisations;

- involve tourism, because it can help you to attract new audiences: spiritual tourism is a new niche market all over Europe;

- at the same time, try to retain the original atmosphere of your tradition and try to combine the cultural aspect of your tradition with the religious one, which is just as important.

Critical reflexion

It is important to stress that the above mentioned success factors build on the heritage care plans of the communities themselves. From the more general perspective of VIE we feel that there are some aspects or dilemmas which need serious consideration. Of these, the possible tension between tourism and religion is perhaps the most important. But also the relation between culture and religion. We are dealing with religious practices which are also valuable from the heritage perspective of UNESCO. As it is put in the text of the convention: ‘The “intangible cultural heritage” means the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills – as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith – that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage.’ All the above mentioned communities recognize their tradition ‘as part of their cultural heritage’. But that the religious aspect also needs consideration goes without saying. How far can you go to ‘culturalise’ your tradition? What is the role of the church officials under whose authority the religious practices were originally performed? It is one thing to say ‘not to restrict yourself to one denomination only and try to disentangle yourself from rigid church structures’ but how far can you go in this without losing the religious meaning of your practice? In this there can be a tension between orthodox and more free interpretations of religion.

Even more this is the case with tourism and intangible heritage. There might well be groups within the community who may not be interested to involve outsiders. Sometimes, as we see in the case of indigenous groups in Africa or India, involvement of outsiders or tourists can pose risks to the tradition bearers. To involve tourism might end up in some kind of ‘staged authenticity’, interesting for tourist but with no direct relevance to the community itself anymore. It is not the intention of the UNESCO convention to preserve your tradition as a museum piece. It should be a living tradition, sustained by the community.

- Driekoningen Zingen in Brabant

- The Blessed Sacrament Procession in Boxmeer

- The Passion Plays in Tegelen

- Children singing from door to door Sint Martin in Utrecht

- Saint Martin a living legend Telling the story anew with comics

- Saint Martin a marvellous spectacle very attractive to tourists

- The Sjaasbergergank Open Air Holy Mass Celebration

- Psalm singing in Genemuiden

- Psalm singing in Genemuiden_2

- All Souls visiting of the graves

One Comment